History

Restoration began in 1984, when I purchased the Onion House in dilapidated condition from my Auntie Dofeen.

by Beth McCormick

Like a ruined Mayan temple overtaken by the rainforest, the Onion House was draped in climbing vines and foliage that masked its distinctive arches. The jungle grows fast in twenty years of neglect.

Whatever mixture of caprice and acumen that inspired my Auntie Dofeen to build and bankroll this extraordinary home did not include the work of maintaining it. That role fell to me.

Whatever mixture of caprice and acumen that inspired my Auntie Dofeen to build and bankroll this extraordinary home did not include the work of maintaining it. That role fell to me.

|

|

I scrambled to buy the place within weeks of foreclosure. Auntie Dofeen had neglected to pay the mortgage in over a year, and her banker had no other options. At thirty years old, this was the first home I’d ever owned, and I had no idea of the amount of work that lay ahead to restore it. My aunt, in a personal decline that mirrored her surroundings, came with the deal.

First things first. The Onion House had become sort of a flop-house for a couple of young Bohemians who’d set up residence in the ruin, alongside Auntie Dofeen. The fellow had hair that belonged onstage in a heavy metal band, and the waif was from Argentina. Neither of them wore any clothes. The Bohemians seemed to resent my showing up every morning, with mop and bucket in hand, disturbing their scene. I determined to be unremittingly friendly so as not to risk reprisals. I cleaned. They watched. I persisted. Reluctantly, they began to get the notion that it was time to move on. I kept cleaning. One night the guy with the rock ‘n roll hair decided he was headed off to Bali, without the waif. She got nasty and threw his electronic keyboard in the swimming pool, which had become a swamp, the color of seaweed and the consistency of pea soup. The keyboard remained in the mire, since no one was willing to fish it out. |

It was always sort of mysterious, what else might have found its way to the bottom of the swamp over the years since it had functioned as a swimming pool. Musical equipment? Bodies? Who knew?

I’d heard stories about the policeman who fell in. He and his buddies snuck up one night, flashlights in hand, to check out this weird ruin that lay abandoned in the jungle. The forces of decay were laying siege while Auntie was on an extended sailing expedition. Trees had taken root in the planters around the pool, breaking apart the masonry, and the entire view of the ocean was blocked by overgrown thickets.

In came the three cops, climbing past the thorny bougainvillea tangle obscuring the entrance steps, shining their flashlights over the still-beautiful arches. Inside, they could see piles of newspaper reaching to the ceiling. (Auntie Dofeen was dedicated to recycling years before it caught on, long before there was anyplace to take the newspapers.) One of the cops pointed his beam down a set of stairs, which he followed, out onto what he took to be a lawn. One step later, and he was in over his head, covered with slime, mired in the murk of what ought to have been a swimming pool. In his starched uniform. With his gun. His buddies howled with mirth, relieved it hadn’t happened to them. The incident became a part of Kona legend, recounted to me on several occasions decades later by members of the local constabulary.

Auntie Dofeen loved all things Hawaiian.

Auntie Dofeen loved all things Hawaiian.

Auntie Dofeen was an eccentric. That’s how I thought of her, as early as kindergarten. The word seemed to define her. Eventually, it came to confine her. Impetuous, impossible, fun, vulnerable, visionary, and lovable... I found her endlessly fascinating.

The daughter of a sea captain and the niece of the McCormick spice company founder, Auntie Dofeen had an affinity for Polynesia and a flair for the exotic. Her father, in his youth, had been a mapmaker for the first scientific expedition to Easter Island in 1886, and from an early age she identified with the mystery and adventure of remote islands. The lure of remote islands was forever in her blood, since she grew up hearing tales about my grandfather's explorations in Borneo, the Philippines, and Easter Island.

At 60, Auntie Dofeen took off in an ill-equipped sailboat along with my two teenage brothers, crossing from Kona to Fanning Island, Palmyra, Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga. This madcap journey was the adventure of a lifetime which they were all lucky to have survived, but the Onion House never really recovered from her absence during those years.

The daughter of a sea captain and the niece of the McCormick spice company founder, Auntie Dofeen had an affinity for Polynesia and a flair for the exotic. Her father, in his youth, had been a mapmaker for the first scientific expedition to Easter Island in 1886, and from an early age she identified with the mystery and adventure of remote islands. The lure of remote islands was forever in her blood, since she grew up hearing tales about my grandfather's explorations in Borneo, the Philippines, and Easter Island.

At 60, Auntie Dofeen took off in an ill-equipped sailboat along with my two teenage brothers, crossing from Kona to Fanning Island, Palmyra, Fiji, Samoa, and Tonga. This madcap journey was the adventure of a lifetime which they were all lucky to have survived, but the Onion House never really recovered from her absence during those years.

It’s hard to imagine how remote Kona was when the Onion House was conceived, in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, before statehood ushered in waves of sun-worshippers and successive building booms. In the old days, when Auntie Dofeen first fell in love with the place, a dog could safely nap in the middle of the road without disturbance. Kailua had only one stop sign, which wasn’t really necessary, but it was prestigious, the only one on the west side of the island. Shopping consisted of the old Taniguchi store, a 20 x 20 foot room stocked with a meager assortment of canned goods, fishing tackle, and rubber slippers.

This was the setting where she was inspired to build her masterpiece. Up on the hillside, safe from tsunamis and storms, she plunked this inconceivable structure. At the time, many Kona folks lived in coffee shacks without indoor plumbing or electricity. To them, it was as bizarre as if she built a space shuttle.

Back on the Mainland, the country was transitioning between the “Father Knows Best” days of the Eisenhower administration, and the Camelot magic of the Kennedy era. News clips were full of the pillbox hats Jackie Kennedy pinned atop her coiffed hair during her shopping trips to Paris.

In stark contrast to the consciousness of the day, Auntie Dofeen was concerned with Organic Architecture and how to grow mangoes. When she first saw Kona, she knew this was the place for her dream to be manifest.

The immediate problem was finding a realtor, and for that she had to make her way back along the windy, single lane road through the cane towns to Hilo (which took all day) where she finally located someone who could help. She wrote a bad check, told him not to cash it, and later recounted that when she got home to San Diego, her banker greeted her with, “So! I see you’ve been to Hawaii!”

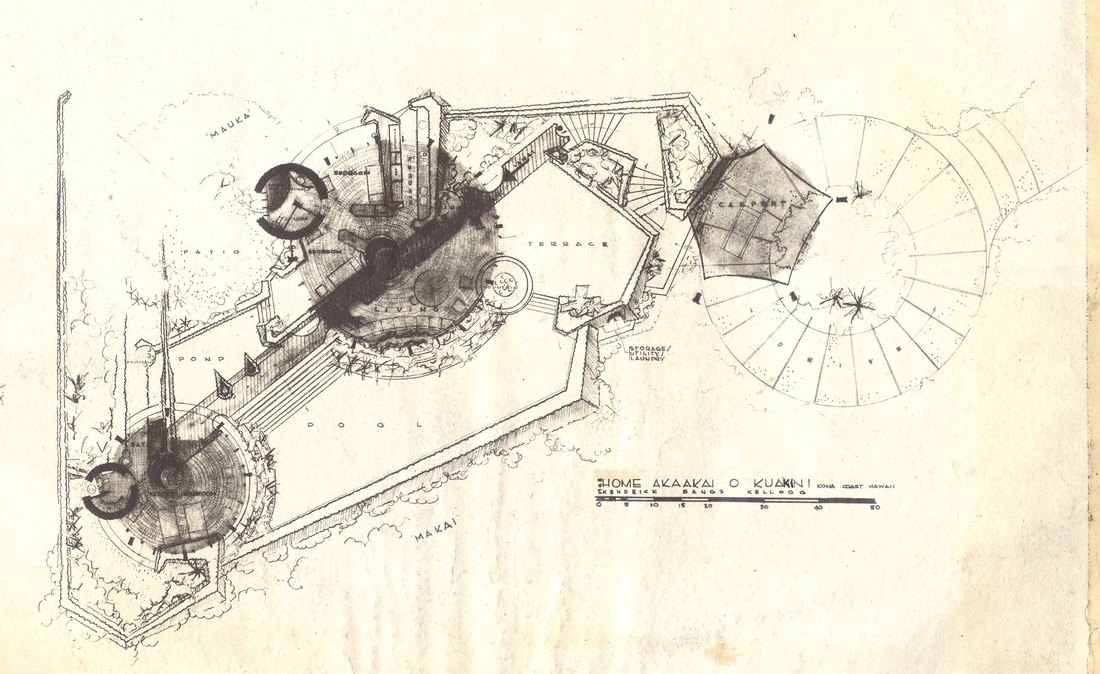

Auntie Dofeen sought out the budding young architect, Kendrick Bangs Kellogg, whose life work would expand the vocabulary of structure beyond any buildings that had yet been conceived. At the time, he had only designed two houses, one for his in-laws, and one for the Babcock family in San Diego. Having seen Kendrick Kellogg’s innovative design for the Babcock house in San Diego, Auntie Dofeen knew immediately that he was the architect she wanted to work with. I would say that their passions overlapped. An idealistic young visionary, Kellogg wanted to create original living spaces in harmony with the natural environment. She needed to live in a piece of art.

She wanted to capture the powerful presence of the Hawaiian sacred spaces, known as heiau, the temple structures formed of raised stone platforms looking toward the sea.

This was the setting where she was inspired to build her masterpiece. Up on the hillside, safe from tsunamis and storms, she plunked this inconceivable structure. At the time, many Kona folks lived in coffee shacks without indoor plumbing or electricity. To them, it was as bizarre as if she built a space shuttle.

Back on the Mainland, the country was transitioning between the “Father Knows Best” days of the Eisenhower administration, and the Camelot magic of the Kennedy era. News clips were full of the pillbox hats Jackie Kennedy pinned atop her coiffed hair during her shopping trips to Paris.

In stark contrast to the consciousness of the day, Auntie Dofeen was concerned with Organic Architecture and how to grow mangoes. When she first saw Kona, she knew this was the place for her dream to be manifest.

The immediate problem was finding a realtor, and for that she had to make her way back along the windy, single lane road through the cane towns to Hilo (which took all day) where she finally located someone who could help. She wrote a bad check, told him not to cash it, and later recounted that when she got home to San Diego, her banker greeted her with, “So! I see you’ve been to Hawaii!”

Auntie Dofeen sought out the budding young architect, Kendrick Bangs Kellogg, whose life work would expand the vocabulary of structure beyond any buildings that had yet been conceived. At the time, he had only designed two houses, one for his in-laws, and one for the Babcock family in San Diego. Having seen Kendrick Kellogg’s innovative design for the Babcock house in San Diego, Auntie Dofeen knew immediately that he was the architect she wanted to work with. I would say that their passions overlapped. An idealistic young visionary, Kellogg wanted to create original living spaces in harmony with the natural environment. She needed to live in a piece of art.

She wanted to capture the powerful presence of the Hawaiian sacred spaces, known as heiau, the temple structures formed of raised stone platforms looking toward the sea.

When he handed her the blueprints for the Onion House, she unrolled them, and studied the drawings, which were unlike any houseplans ever seen. Scrutinizing the plans until she understood what it was Kellogg was proposing to create, she rolled them up and handed them back to him. Pausing to light a cigarette, she leaned back, and said, “Build it!”

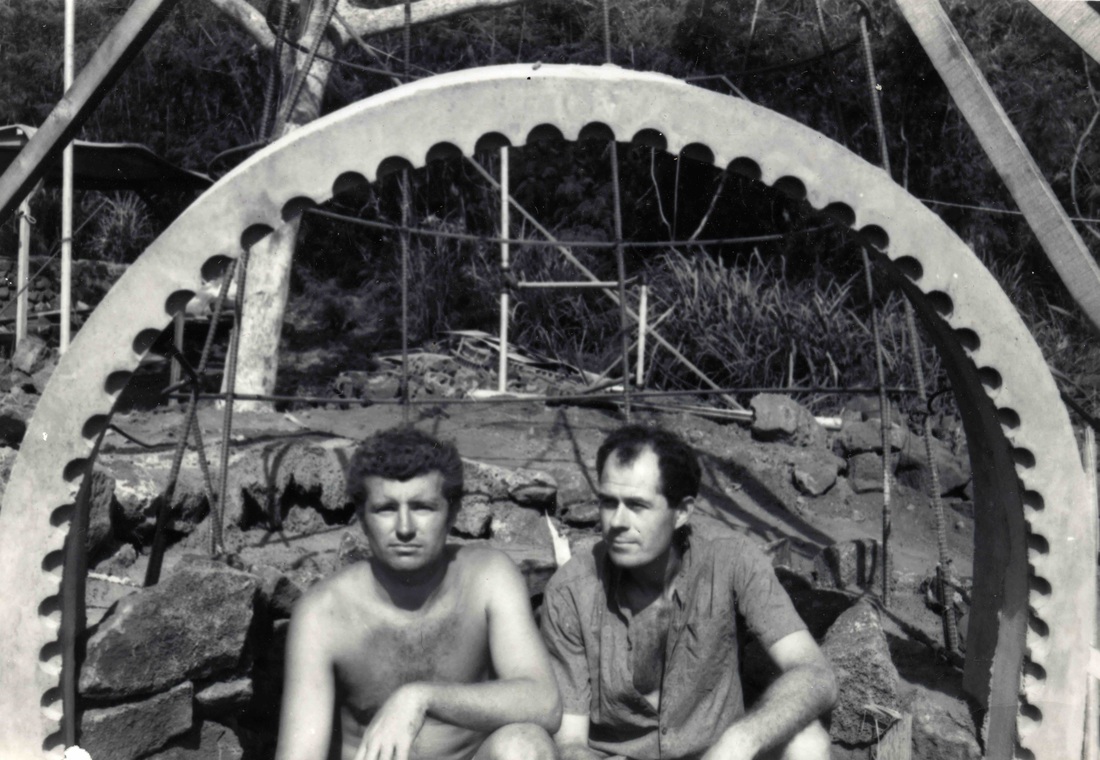

The problem was finding a contractor. Everybody they sent it to sent the plans back, saying it couldn’t be done. Kellogg’s visionary design for the Onion House was so wild that they were unable to find anyone willing to attempt construction.

Rather than letting the project go, Kellogg moved to Kona with his wife and young children for two years to build the home himself. He brought in William Slatton, metal worker for Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West, who forged the gate and spires. James Hubbell came over to create the stained mosaic dining room table, and the colorful stained glass windows that enliven the space. Together, they helped to influence the movement known as Organic Architecture.

The problem was finding a contractor. Everybody they sent it to sent the plans back, saying it couldn’t be done. Kellogg’s visionary design for the Onion House was so wild that they were unable to find anyone willing to attempt construction.

Rather than letting the project go, Kellogg moved to Kona with his wife and young children for two years to build the home himself. He brought in William Slatton, metal worker for Frank Lloyd Wright at Taliesin West, who forged the gate and spires. James Hubbell came over to create the stained mosaic dining room table, and the colorful stained glass windows that enliven the space. Together, they helped to influence the movement known as Organic Architecture.

On the island, there was no way to get supplies, unless you arranged to ship them yourself from the Mainland. There was plenty to do while waiting for the barge to arrive with the Italian tile, plumbing fixtures, and redwood, amid sheets of colored glass. Koa wood and lava rock were available locally. Kellogg bought the essentials: an old truck, a cement mixer, a wheelbarrow and a shovel.

Auntie Dofeen’s husband at the time, my Uncle George, a (somewhat) practical man, did not share her passion for this project. He refused to even set foot on the island. This led to an understandable rift between them, but did not undermine her determination. Part seer, part daft eccentric, Auntie Dofeen’s abiding characteristic was enthusiasm.

They had a unique relationship for the 1950’s: she worked for the Navy Electronics Lab in San Diego, and he stayed home and took care of the canaries. (She had built an extensive aviary, needing constant care, which was where I first fell in love with feathers.)

Kendrick Kellogg recounts that in those days, when he was still wet behind the ears, he brought the plans for the Onion House to Auntie Dofeen’s home in San Diego. When Uncle George saw the young Kellogg, with an armful of blueprints, he glowered, “So kid, you’re a BUILDER now, too?”

The anecdote is told with humor and a whiff of nostalgia, but the point remains. They were both pushing the envelope, far beyond the levels of what anybody was comfortable with, in order to prove what was do-able.

Auntie Dofeen’s husband at the time, my Uncle George, a (somewhat) practical man, did not share her passion for this project. He refused to even set foot on the island. This led to an understandable rift between them, but did not undermine her determination. Part seer, part daft eccentric, Auntie Dofeen’s abiding characteristic was enthusiasm.

They had a unique relationship for the 1950’s: she worked for the Navy Electronics Lab in San Diego, and he stayed home and took care of the canaries. (She had built an extensive aviary, needing constant care, which was where I first fell in love with feathers.)

Kendrick Kellogg recounts that in those days, when he was still wet behind the ears, he brought the plans for the Onion House to Auntie Dofeen’s home in San Diego. When Uncle George saw the young Kellogg, with an armful of blueprints, he glowered, “So kid, you’re a BUILDER now, too?”

The anecdote is told with humor and a whiff of nostalgia, but the point remains. They were both pushing the envelope, far beyond the levels of what anybody was comfortable with, in order to prove what was do-able.

The controversial building project six decades ago in this tiny local community inspired much speculation. One woman was overheard to say disparagingly, “The damned thing looks like an onion!” Word got back to Auntie Dofeen, whose immediate reaction was “Eureka! That’s IT! The Onion House!” She loved onions, and reasoned that since the construction was partially financed by the sale of McCormick dehydrated onions, the name was only fitting.

The housewarming party lasted for three days and three nights. Auntie Dofeen noted that the stone walls surrounding the terrace seat fifty nicely. She had invited all of Kona.

The housewarming party lasted for three days and three nights. Auntie Dofeen noted that the stone walls surrounding the terrace seat fifty nicely. She had invited all of Kona.

Auntie Dofeen loved animals. The local vet would send her wounded and disheveled creatures, and she at one time had twelve adopted dogs and thirteen cats. A hunter gave her a baby goat whose mother had been killed, and the goat suckled right along with a litter of puppies. The goat grew up thinking it was a dog. It ate Little Friskies and chased cars, along with the rest of the pack.

She drove a brand new red Mercedes 350 SEL, which she chronically neglected to maintain. Too short to see over the wheel, she peered out a narrow arched portal underneath the steering wheel and above the dashboard, so from the outside, only the top of her head, wearing a large cluster of hibiscus flowers, was barely visible. Crusted in a layer of brown dust, its paint color unrecognizable, the Benz would cruise by with apparently nobody driving, its leather seats overflowing with her collection of happy mongrels.

Eventually, the Benz stopped running. She had never changed the oil.

With her love of all things Polynesian, Auntie Dofeen counted among her drinkin’ buddies a number of Hawaiians, including one large and jovial man known as ‘Uncle Bull.’ I remember as a child being fascinated by the sound of his snores, after he passed out on a bench at the Onion House. It was Auntie Dofeen’s idea to tie a long string around his big toe. The two of us hid outside in the planter, stifling our laughter, and jerked on the string. He would awaken bellowing exactly like a bull, gazing around the empty room, confounded. As soon as he settled back into his stupor, we would gleefully give another tug on our instrument of torment.

Another of her Hawaiian friends was I’olani Luahine, the renowned hula dancer who lived at Hulihe’e Palace, the royal residence of Hawaiian monarchs on Kailua Bay, as the kahu. (In Hawaiian, ‘kahu’ means keeper or guardian, as in kahuna, which means ‘keeper of the secret knowledge;’ ‘kahu’ of the ‘huna.’) Auntie I’olani was a tiny, ever-mischievous dark-skinned sprite with eyes that shot fire, who would always greet us with elaborate ritual. Like an emissary from another world, she chanted to invoke the gods, sinuously dancing her way toward us for an ecstatic embrace. This might be, say, mid-morning if we happened to see her at the post office. This made perfect sense to Auntie Dofeen, because, after all, I’olani had been given to Laka, the goddess of the dance, at her birth. I later came to realize how much I’olani Luahine was esteemed in the Hawaiian community, although she frightened some who felt that she was “spooky” because she was taught to dance by the spirit world. Aunt Dofeen accepted that the spirit world expressed itself through I’olani.

Perhaps this understanding was the bond that made them such amiable drinkin’ buddies. Even now, at the Merry Monarch Festival, amid that explosion of Hawaiian hula, one dancer among hundreds for a moment has it, that salty, earthy, electric energy that I’olani channeled continually. At 70, her high-voltage eroticism in the hula could stir something inside you that you didn’t know was there.

Auntie Dofeen and Auntie I’olani Luahine both were kahu of their respective heritages. This responsibility did not extend to mundane physical maintenance, obviously, but they both were dedicated to the preservation of a spiritual essence that was fundamental to their respective landmark residences.

As the jungle engulfed the Onion House estate, they frolicked through it. Whatever decline eventually claimed these unforgettable souls, they lived their moments with a sense of profound celebration rarely seen in the more responsible among us.

My work of stewarding the Onion House has been a tribute to the sense of flamboyant joy that inspired its creation.

She drove a brand new red Mercedes 350 SEL, which she chronically neglected to maintain. Too short to see over the wheel, she peered out a narrow arched portal underneath the steering wheel and above the dashboard, so from the outside, only the top of her head, wearing a large cluster of hibiscus flowers, was barely visible. Crusted in a layer of brown dust, its paint color unrecognizable, the Benz would cruise by with apparently nobody driving, its leather seats overflowing with her collection of happy mongrels.

Eventually, the Benz stopped running. She had never changed the oil.

With her love of all things Polynesian, Auntie Dofeen counted among her drinkin’ buddies a number of Hawaiians, including one large and jovial man known as ‘Uncle Bull.’ I remember as a child being fascinated by the sound of his snores, after he passed out on a bench at the Onion House. It was Auntie Dofeen’s idea to tie a long string around his big toe. The two of us hid outside in the planter, stifling our laughter, and jerked on the string. He would awaken bellowing exactly like a bull, gazing around the empty room, confounded. As soon as he settled back into his stupor, we would gleefully give another tug on our instrument of torment.

Another of her Hawaiian friends was I’olani Luahine, the renowned hula dancer who lived at Hulihe’e Palace, the royal residence of Hawaiian monarchs on Kailua Bay, as the kahu. (In Hawaiian, ‘kahu’ means keeper or guardian, as in kahuna, which means ‘keeper of the secret knowledge;’ ‘kahu’ of the ‘huna.’) Auntie I’olani was a tiny, ever-mischievous dark-skinned sprite with eyes that shot fire, who would always greet us with elaborate ritual. Like an emissary from another world, she chanted to invoke the gods, sinuously dancing her way toward us for an ecstatic embrace. This might be, say, mid-morning if we happened to see her at the post office. This made perfect sense to Auntie Dofeen, because, after all, I’olani had been given to Laka, the goddess of the dance, at her birth. I later came to realize how much I’olani Luahine was esteemed in the Hawaiian community, although she frightened some who felt that she was “spooky” because she was taught to dance by the spirit world. Aunt Dofeen accepted that the spirit world expressed itself through I’olani.

Perhaps this understanding was the bond that made them such amiable drinkin’ buddies. Even now, at the Merry Monarch Festival, amid that explosion of Hawaiian hula, one dancer among hundreds for a moment has it, that salty, earthy, electric energy that I’olani channeled continually. At 70, her high-voltage eroticism in the hula could stir something inside you that you didn’t know was there.

Auntie Dofeen and Auntie I’olani Luahine both were kahu of their respective heritages. This responsibility did not extend to mundane physical maintenance, obviously, but they both were dedicated to the preservation of a spiritual essence that was fundamental to their respective landmark residences.

As the jungle engulfed the Onion House estate, they frolicked through it. Whatever decline eventually claimed these unforgettable souls, they lived their moments with a sense of profound celebration rarely seen in the more responsible among us.

My work of stewarding the Onion House has been a tribute to the sense of flamboyant joy that inspired its creation.